Summerer

„The Beginnings of Drug Therapy: Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine“ Drug News & Perspectives von John K. Borchardt (2002) 15 (3): 187–192 doi:10.1358/dnp.2002.15.3.840015. ISSN 0214-0934. PMID 12677263. Many Sumerian (late 6th millennium BC – early 2nd millennium BC) cuneiform clay tablets record prescriptions for medicine.

Transkript von Ancient Sumerian Medicine

Before Sumerian medicine was invented, many Sumerians died of diseases and injuries. They later learned how to heal and treat their inuries and cure their sicknesses.

Impact on today

After they had medicine, people were living a little longer. Diseases were cured and injuries were treated.

Religion and Medicine

The ancient Sumerians believed that gods and demons caused diseases. They would try to cure diseases by making charms and casting spells.

They thought that the gods would put diseases on people if they sinned or did something wrong. By about 2500 BCE, doctors in Sumer started prescribing medical treatments.

Medicine was used to cure people of disease and heal their injuries. The Sumerians used natural items, such as parts of plants and animals. For example, they used sesame oil as an anti-bacterial. They mixed it in with plasters. They used plasters to heal injuries. The mixture they used to make plaster had ingredients that cleaned and healed injuries.

Lilly Kelley / Morgan Engel

Ancient Sumerian Medicine

Uses

In Sumer, there were two types of doctors: asu and ashipu.

The ashipu, sometimes called a „sorcerer,“ tried to find out what demon or god was causing the sickness. They also tried to find out what sin the person comitted to get the disease.

Ashipu. The impact it had on today is that we have a lot of medical advances. Now we have medicine for headaches so people aren’t cutting into peoples heads and people are living a lot longer than the Sumerians did.

Asu

The asu used herbal remedies to cure diseases. Their three main techniques were: washing, bandaging, and making plasters.

Trephination

Trephination is a procedure where the Sumerians would cut a hole in ones head. The hole would relieve pressure on the brain.

Trephination is still around today. It has just evolved. Doctors can drill holes in patients head to stop blood clots and to take pressure off of the brain or skull.

Works Cited

http://www.indiana.edu/~ancmed/meso.HTM

Mixture- http://www.sitchin.com/adam.htm

http://www.wikihow.com/Administer-Medicine-to-a-Resistant-Child

Clay Tablets- http://www.bibleandscience.com/store/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=344

Medical records

were kept on clay

tablets.

Left: Sumerian medical clay tablet – Medical clay tablet from Nippur dated to about 2200 BC is considered the oldest known Sumerian medical book. 2200 BC. Source: Samuel N. Kramer, History begins at Sumer; Right: Treatment of a patient

Among the more than 30,000 surviving cuneiform tablets, approximately a thousand of them deal with medicine and medical practices of the Sumerians.

Many of the tablets comes from the ancient city of Uruk (2,500 BC) but most of this knowledge recorded on more than 600 tablets, comes from the famous library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668 BC), Assyria.

The “Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses” is one of the largest and the oldest (around 1,600 BC) sources recorded on 40 tablets collected and studied by the French scholar R. Labat.

It contains a mixture of several centuries of Mesopotamian medical knowledge of pediatrics, gynecology and convulsive disorders, neurology, skin diseases, fevers and many more, with descriptions of accurately observed symptoms. Some of the treatments (such as certain bleedings) can be easily compared to those applied even today.

The Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century BC claimed that the Babylonians had no physicians and this claim is definitely incorrect.

The existence of a profession of medicine is well attested throughout Mesopotamian history including the famous ‘Laws of Hammurabi of Babylon’ regulating the practice of medicine, fixing medical fees, and the penalties for failure, which were severe.

God of underworld, Nergal instructs a lion-demon in the punishment of a sinner; it’s a graphic interpretation of seizure of disease from a cylinder seal of the Old Babylonian Period.

‚.. A doctor was to be held responsible for surgical errors and failures. Since the laws only mention liability in connection with “the use of a knife,” it can be assumed that doctors in Hammurabi’s kingdom were not liable for any non-surgical mistakes or failed attempts to cure an ailment. […] both the successful surgeon’s compensation and the failed surgeon’s liability were determined by the status of his patient.

‘… if a surgeon operated and saved the life of a person of high status, the patient was to pay ten shekels of silver. If the surgeon saved the life of a slave, he only received two shekels. However, if a person of high status died as a result of surgery, the surgeon risked having his hand cut off. While if a slave died from receiving surgical treatment, the surgeon only had to pay to replace the slave…“

here were two kinds of doctors: the Asu – herbal practitioner skilled in using minerals and a variety of resins, spices and plants with antibiotic and/or antiseptic properties.

The medical library of Ashurbanipal, for example, had lists of more than 250 vegetable substances and over 120 minerals substances with ascribed medical properties and how they have been used to treat certain illnesses.

Asu treated wounds by washing, bandaging and creating the first plaster derived from a mixture of medical and herbal ingredients, which were very important for medical treatment.

Another doctor was the Asipu (Ashipu) – a healer who had to determine which god or demon was causing the patience’s illness and whether the illness was the result of some error or sin of the patient. Diverse spells and charms were usually prescribed by the Asipu.

There were also specialized surgeons with medical background and veterinarians (who also could be either Asu or Asipu). Dentistry was practiced by both kinds of doctors and both may have also assisted at births.

The doctors used a physical examination of the patient and checked temperature, pulse and reflexes. All medicines in Mesopotamia were made by women. Quelle AncientPages.com | November 20, 2017 |

A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Medicine has a long history in the Middle and Near East. The earliest known medical records go back to the ancient Mesopotamia and begin in Sumer about 3,000 BC.

Left: Sumerian medical clay tablet – Medical clay tablet from Nippur dated to about 2200 BC is considered the oldest known Sumerian medical book. 2200 BC. Source: Samuel N. Kramer, History begins at Sumer; Right: Treatment of a patient.

Among the more than 30,000 surviving cuneiform tablets, approximately a thousand of them deal with medicine and medical practices of the Sumerians.

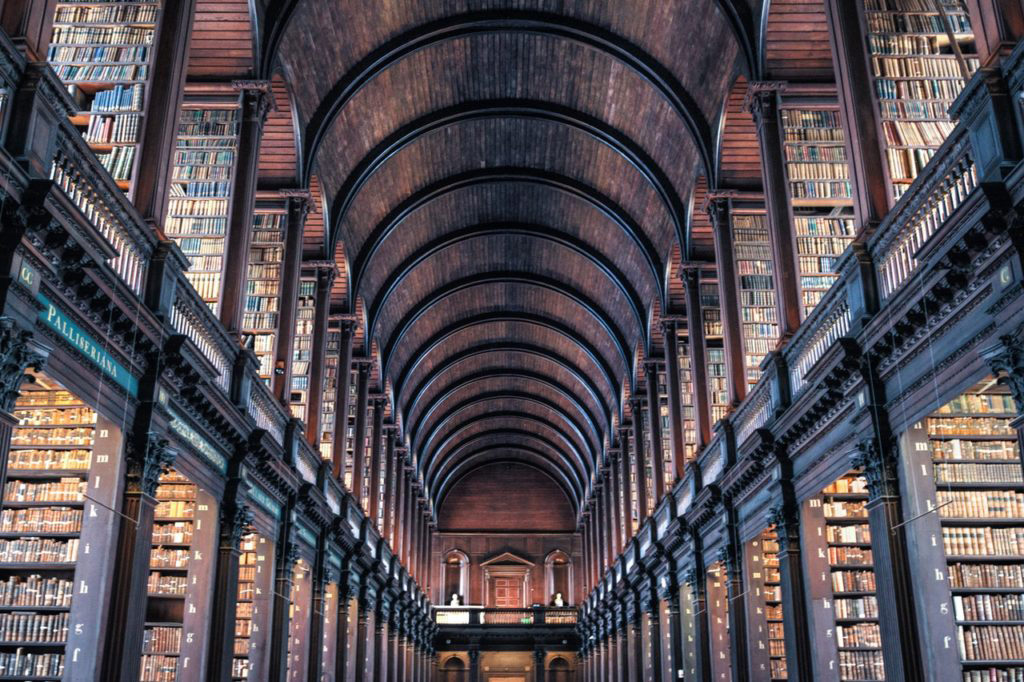

Many of the tablets comes from the ancient city of Uruk (2,500 BC) but most of this knowledge recorded on more than 600 tablets, comes from the famous library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668 BC), Assyria.

The “Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses” is one of the largest and the oldest (around 1,600 BC) sources recorded on 40 tablets collected and studied by the French scholar R. Labat.

It contains a mixture of several centuries of Mesopotamian medical knowledge of pediatrics, gynecology and convulsive disorders, neurology, skin diseases, fevers and many more, with descriptions of accurately observed symptoms. Some of the treatments (such as certain bleedings) can be easily compared to those applied even today.

The Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century BC claimed that the Babylonians had no physicians and this claim is definitely incorrect.

There were two kinds of doctors: the Asu – herbal practitioner skilled in using minerals and a variety of resins, spices and plants with antibiotic and/or antiseptic properties.

The medical library of Ashurbanipal, for example, had lists of more than 250 vegetable substances and over 120 minerals substances with ascribed medical properties and how they have been used to treat certain illnesses.

Asu treated wounds by washing, bandaging and creating the first plaster derived from a mixture of medical and herbal ingredients, which were very important for medical treatment.

Another doctor was the Asipu (Ashipu) – a healer who had to determine which god or demon was causing the patience’s illness and whether the illness was the result of some error or sin of the patient. Diverse spells and charms were usually prescribed by the Asipu.

There were also specialized surgeons with medical background and veterinarians (who also could be either Asu or Asipu). Dentistry was practiced by both kinds of doctors and both may have also assisted at births.

The doctors used a physical examination of the patient and checked temperature, pulse and reflexes. All medicines in Mesopotamia were made by women.

A practical knowledge of many herbal remedies, as well as some surgical knowledge existed in ancient Mesopotamia; the causes of diseases were not entirely understood.

The Sumerians believed that not only the people but also the gods could be ill and the Sumerian writings mention the case of the chief physician, god Enki and his disease treated by the goddess Ninhursag.

Among ordinary people, many diseases were often ascribed to the work of gods, demons and had names such as ‚the hand of a ghost’, ‘the hand of god’, ‚the hand of Istar’ (Inana)‘, ‚the hand of Samas (Utu)‘ or ‘the hand of the demon Lamashtu is upon her’. Lamashtu, was an awful she-demon of disease and death and the daughter of the supreme god Anu,

Certain demons and evil spirits acted as the representatives of gods, for the punishment of sin.

Especially illnesses, which could today be regarded as ‘psychological’ were considered as the world of demons or result of sorcery.

Later, the Babylonians made several advances in medicine. They recorded medical history of the patients in order to diagnose to be able to diagnose and treat illnesses. Diverse pills, creams and herbal mixtures based on syrup and honey, were widely used.

Clay tablets covered with cuneiform signs and seals that were used by doctors of ancient Mesopotamia give us important clues to early knowledge of medicine in this region of the world.

Much of this information is still valid and used even today in some of modern medical prescriptions.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

The Largest Surviving Medical Treatise from Ancient Sumerian medical tablet (2400 BC), ancient city of Nippur. Lists 15 prescriptions used by a pharmacist. Library of Ashurbanipal.

Because clay tablets, especially those baked in fires, were more durable than papyrus rolls, more original source material regarding medicine survived from Mesoptomia than from ancient Greece or Rome. Even though the amount of surviving medical textual information from Mesopotamia may be greater than what survived from Egypt, comparing the quantities of the two sources of ancient medical information is complicated since, in addition to the medical papyri which survived in the hospitable climate of Egypt, Egyptian mummies represent a unique source of paleopathological information that is not textual.

The surviving Mesopotamian medical records consist of roughly 1000 cuneiform tablets, of which 660 medical tablets from the library of Ashurbanipal are preserved in the British Museum. About 420 tablets from other sites also survived, including the library excavated from the private house of a medical practitioner (Asipu) from Neo-Assyrian Assur, and some Middle Assyrian and Middle Babylonia texts.

Most of these Mesopotamian medical tablets were not discovered until the nineteenth century, and because of difficulties with translation of cuneiform script, many of these tablets were not understood by scholars until recently. Another factor that must be taken into consideration is that since these tablets survived by unintended burial rather than by manuscript copying, and they were not preserved until comparatively recently in conventional libraries or museums, the medicine they record did not necessarily play a conventional role in the Western medical tradition. What influence their contents might have had on the practice of later physicians remains unclear.

The medical texts from Asurbanipal´s library were first published in facsimile by Reginald Campbell Thompson as Assyrian Medical Texts. From the Originals in the British Museum (1923). Franz Kocher later published six volumes called Die babylonisch-assyrische Medizin in Texten und Untersuchungen (1963-1980), the first four volumes of which contain the tablets found from sites other than Assurbanipal’s library.

„The remaining two volumes of Kocher’s work augment Campbell Thompson, providing new joins of broken fragments and much material uncovered in the British Museum. At least one more volume of Nineveh texts has been announced. In addition, the series Spaet Babylonische Texte aus Uruk contains some 30 medical texts not included in Kocher’s work. The vast majority of these tablets are prescriptions, but there are a few series of tablets that contained entries that were directly related to one another, and these have been labeled ‚treatises‘ “ Nancy Demand, The Asclepion accessed 05-30-2009).

More recently the texts of many of the Mesopotamian medical tablets were translated and analyzed from the medical point of view by Assyriologist/cuneiformist, JoAnn Scurlock and physician/medical historian Burton R. Anderson as Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine (2005).

•The largest surviving medical treatise from ancient Mesopotamia is known as the Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses

„The text of this treatise consists of 40 tablets collected and studied by the French scholar R. Labat. Although the oldest surviving copy of this treatise dates to around 1600 BCE, the information contained in the text is an amalgamation of several centuries of Mesopotamian medical knowledge. The diagnostic treatise is organized in head to toe order with separate subsections covering convulsive disorders, gynecology and pediatrics. It is unfortunate that the antiquated translations available at present to the non-specialist make ancient Mesopotamian medical texts sound like excerpts from a sorceror’s handbook. In fact, as recent research is showing, the descriptions of diseases contained in the diagnostic treatise demonstrate a keen ability to observe and are usually astute. Virtually all expected diseases can be found described in parts of the diagnostic treatise, when those parts are fully preserved, as they are for neurology, fevers, worms and flukes, VD and skin lesions. The medical texts are, moreover, essentially rational, and some of the treatments, as for example those designed for excessive bleeding (where all the plants mentioned can be easily identified), are essentially the same as modern treatments for the same conditions“accessed 05-30-2009).

Traditionelle Chinesische Medizin

Die Medizin des Gelben Kaisers – Das Huángdì Nèijīng

Die Daoisten sagten ihm nach, das Buch Die Medizin des Gelben Kaisers (黃帝內經 / 黄帝内经, Huángdì Nèijīng), geschrieben zu haben. Das Huángdì Nèijīng enthielt das damalige Wissen über Akupunktur, Akupressur und andere Teilbereiche der traditionellen chinesischen. Dieses Werk umfasst eine Sammlung von 81 Abhandlungen, die in zwei Büchern zusammengefasst sind – dem Su Wen – Fragen organischer und grundlegender Art – und dem Ling Shu – „Göttlicher Angelpunkt“, mit eher technischen Aspekten der Akupunktur. Im ersteren finden sich Dialoge des Gelben Kaisers mit den Gelehrten seines Hofes, in denen er die Fragen über Physiologie, Morphologie, Pathologie, Diagnose und der für die antike chinesische Medizin vorrangige Kranheitzprävention erläutert. Im Ling Shu wird die klinische Anwendung der Akupunktur und Moxibustion, sowie die Lage der Akupunkturpunkte und der Meridiane beschrieben.

In dem Hauptwerk lassen sich Ideen sowohl aus dem Daoismus wie auch aus dem Konfuzianismus finden. Heute gilt das Buch als eine Kompilation aus der Zeit um 300 v. Chr.

Shang Han Lun von Zhang Zongjing/ Zhang Zhong Jing

Bencao gangmu (chinesisch 本草綱目 / 本草纲目, Pinyin Běncǎo Gāngmù, W.-G. Pen3-ts’ao3 Kang1-mu4 ‚Das Buch heilender Kräuter‘) von Li Shizhen (李时珍 / 李時珍) (1518–1593)

Shennong ben cao jing Das Shennong Bencaojing (chinesisch 神農本草經 / 神农本草经, Pinyin Shénnóng Běncǎojīng, W.-G. Shen2-nung2 Pen3-ts’ao3 Ching1 ‚Heilkräuterklassiker nach Shennong‘) ist ein chinesisches Buch über Ackerbau und Heilpflanzen. Die Autorschaft wurde dem mythischen chinesischen Urkaiser Shennong zugeschrieben, der etwa 2800 v. Chr. gelebt haben soll; es wäre demnach das älteste bekannte Buch über Ackerbau und Heilpflanzen. Tatsächlich dürfte das Werk um einiges jünger sein, die meisten Forscher vermuten eine Abfassung zwischen 300 v. Chr. und 200 n. Chr. Das Originalbuch ist nicht mehr erhalten und soll aus drei Bänden bestanden haben, die verschiedene Heil- und Arzneipflanzen dargestellt haben.

Dabei behandelte der erste Band 120 Arzneimittel, die für den Menschen ungiftig und stärkend sind. Behandelt wurde hier etwa der Glänzende Lackporling, Ginseng, Jujube, die Orange, die Zimtkassie, die Ackerdistel und das Süßholz.

Band 2 widmete sich 120 weiteren Arzneistoffen, die auf Körperfunktionen einwirken und teilweise auch giftig sind. Sie werden als menschlich bezeichnet. Darunter fallen der Ingwer, die Pfingstrosen, die Tigerlilie, der Tüpfelfarn Polypodium amoenum und die Schlangengurke.

Der dritte Band schließlich stellte 125 Arzneimittel dar, die heftig auf die Körperfunktionen wirken und meist giftig sind. Diese Stoffe werden als irdisch bezeichnet und dürfen nicht länger eingenommen werden. Hierzu gehören nach Shennong der Rhabarber, verschiedene Eisenhut-Arten und auch die Kerne des Pfirsich.

Eine vollständige Übersetzung des Werkes enthält die vierbändige Beschreibung Chinas von Jean-Baptiste Du Halde[1], Li Shizhen übernahm nur 347 der ehemals 365 Arten von Arzneipflanzen in seinem Bencao gangmu, welches vor etwa 400 Jahren erschien. Emil Bretschneider, ein russischer Arzt des 19. Jahrhunderts beschreibt, dass die Pflanzen und ihre Wirkungen aus Shennong’s Beschreibung auch zu seiner Zeit noch allgemein bekannt waren und Verwendung fanden.

Ayurvedische Schriften

Atharvaveda

Die Atharvaveda ist ein von vier Veden (heilige Schriften und Grundlagen des Hinduismus) Eine Ansammlung von Liedern und magischen Sprüchen für Heilrituale und die älteste Textsammlung zur altindischen Heilkunst.

Shusruta Samhita

Caraka Samhita